Why are there so many struggling readers?

Since the pandemic, schools have been engaged in conversation about learning loss and the impact of virtual learning on our students. Federal and state governments provided funding for schools to combat this loss and close the gap. Over the last year, the dip in NAEP scores led to an outcry that schools are doing the “wrong thing” when it comes to reading instruction.

The conversation around reading instruction gained momentum after journalist Emily Hanford published articles before the pandemic, like this one, and then last year with her Sold a Story podcast. In her podcast she posits that teachers have been using practices that are not research based, and as a result we have developed a nation of poor readers. She villainizes Marie Clay, Irene Fountas, Gay Su Pinnell, and Lucy Calkins. She also makes the claim that Reading Recovery, whole language, balanced literacy, and Leveled Literacy Instruction are all improper ways to teach readers because they utilize strategies that encourage students to guess in order to make meaning of words in text rather than have an understanding of the word itself. Her interviews include teachers and parents ridden with guilt over the disservice that has been done to children, particularly since we have abandoned phonics instruction when we should be following “The Science of Reading.”

The message from her podcast spread like wildfire last year. Schools questioned their programs. Teachers questioned their practice. Parents demanded change. Politicians began to develop policies to ensure that schools stop “teaching students the wrong way” and “start using the Science of Reading.” Some state politicians and/or state education departments have even gone as far as mandating what programs schools can use for reading instruction.

In an educational landscape where the pendulum seems to regularly swing back and forth, all this information leaves teachers wondering … What is the truth? What am I doing wrong? What can I do better?

As with any instructional shift, it’s important for us to be critical consumers of information. As is typical in any situation but particularly in education, there are no simple answers because reading is a complex, cognitively demanding process and as a result there isn’t one simple way to develop strong readers.

Is the “Science of Reading” the answer?

You may have heard that students struggle as readers because schools are not using the Science of Reading. But what does that mean? The conversation from politicians implies that the Science of Reading is a thing or a program. As you listen to Hanford’s podcast or read her articles, the Science of Reading seems to mean phonics instruction.

The truth is, the “science of reading” is a body of research that analyzes what needs to happen to help a reader connect oral language to print so that you can read written language. It is not a program, a method, or phonics alone. Which means that the science of reading is part of the answer, but also means that there are instructional practices we have used that are aligned to reading research.

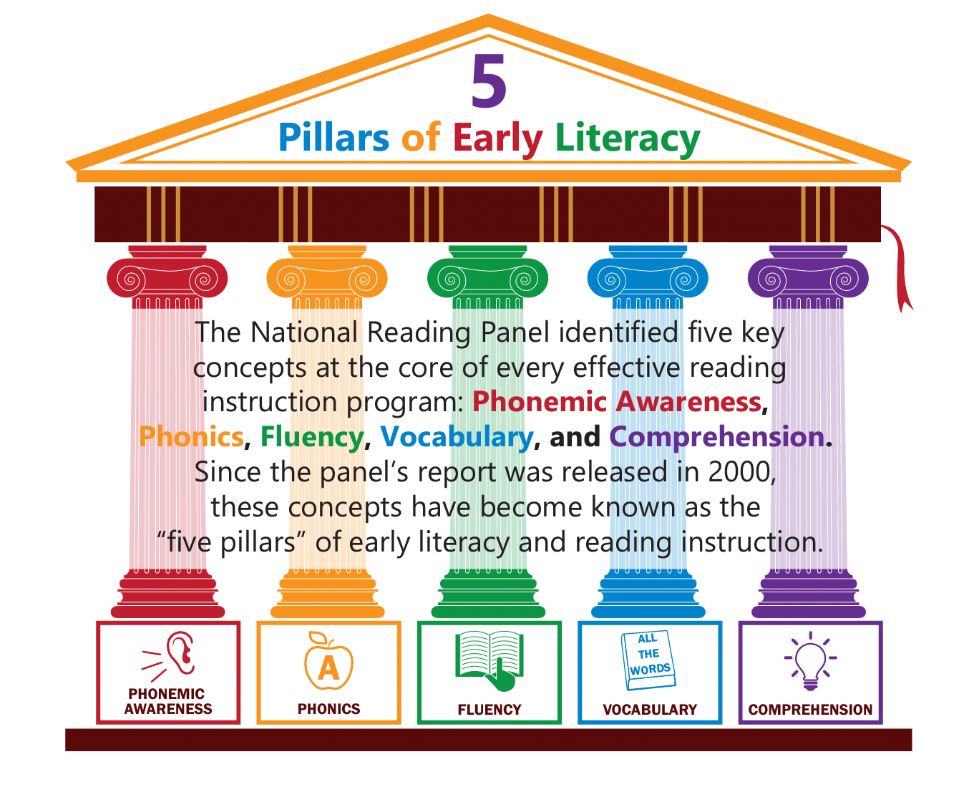

Over two decades ago the National Reading Panel published a report that discussed effective, evidence-based practices for reading instruction, which included identifying “five pillars” of comprehensive practice: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Educators can use this information as they plan instruction to ensure that the lessons they design will help students grow as readers.

Instructional Practices That Build Strong Readers

Phonemic Awareness is understanding what sounds you hear in words. In classrooms at the primary level, students participate in activities to help them identify and manipulate the sounds they hear in words. This includes identifying individual sounds in words, blending sounds together to make words, and/or changing sounds in parts of the word to make new words. This oral language practice is natural for the brain to do, as well as an important skill for students to have as they encounter unfamiliar words.

Phonics is the practice of connecting sounds (phonemes) to letters (graphemes) in order to read words. The ability to connect what we hear to what we see in print is not natural to the brain, therefore we must have students engage in regular, systematic practices to “wire” the brain for print. This practice is called orthographic mapping, and is important for all readers, not just struggling readers.

Fluency is how smoothly we read. Sometimes it is mistaken for how fast we read, but effective fluency is actually represented by three things: accuracy, rate, and prosody. Strong readers should make few mistakes (accuracy), read written text in the same way we speak (rate), and read with expression based on the grammatical cues and structure of a text (prosody).

Vocabulary is the ability to understand the words in a text. As readers we encounter three tiers of words. Tier 1 words as those that are most common in everyday conversation. Tier 2 words are often known as “academic vocabulary” because they are words that occur regularly in text, can be used across content areas, and may have multiple meanings depending on the context (i.e., maintain, consume, perform, adjust, report). Tier 3 words are known as “domain specific” words because the vocabulary is directly connected to a content area (e.g., simile, hypotenuse, photosynthesis).

Comprehension is the ability to make meaning of the texts we read. Strong readers are able to develop the comprehension not only by knowing the words in the text, but also using their background knowledge to understand what the text is saying.

The amount of time focused on each of these pillars will vary depending on the age / grade / ability level of the student, but all are necessary to develop the skills they need to become strong readers.

Next Steps

Educators should not feel that they have been doing everything wrong, throw out all their lesson plans, and start fresh. As I continue to do my own research, I feel affirmed about the good work I’ve done with students in the past but also consider better practices to use in the future. If you want to learn more about including evidenced based practices in your own teaching, I would recommend both Shifting the Balance texts: grade K-2 written by Jan Burkins and Kari Yates and grade 3-5 written by Katie Egan Cunningham, Jan Burkins, and Kari Yates. Their books are structured in a way that explains the research, identifies common misunderstandings, and then provides instructional shifts that are supported by the research. Because they are also educators, the tone of the books are encouraging and teacher friendly, and their website also provides resources that support their recommended shifts.

Ultimately, the most important thing, in the words of Maya Angelou, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then, when you know better, do better.” We can acknowledge that there were things we’ve done wrong, particularly in the systematic way we teach students to read and understand words. We can affirm that there are evidenced-based strategies we are using in our classrooms to build strong readers. And we can move forward doing better for our students if we sort through the rhetoric and noise and focus on research-based practices that are in the best interest of our students.